What’s Your Name?

What's Your Name?

By Jordan Hattar

“Hi, what’s your name?”

It’s just that easy to begin to learn someone’s story.

What happens when we fail to ask someone their name and, instead, assign a name to them?

When I asked a group of young Syrian men in the Zaatari Refugee Camp in the country of Jordan what they needed most, they replied, “Shaving razors.” Puzzled, I asked why. They responded, “So we don’t look like Daesh.” Daesh is the Arabic acronym for ISIS.

Despite mainstream media and politicians warning that we should be fearful of refugees, of the hundreds of refugee families I’ve met, not one of them supported ISIS.

Another example took place at a school in South America. A 7th-grade boy was telling his teacher about the computer game called Minecraft. While attempting to explain the game in more detail the student said, “ya know the terrorists, the Muslims.” Following this comment, the teacher and I led a discussion about how terrorists come from all religions, ethnic groups, shapes and sizes.

The next day a student from that class approached me saying, “I am Muslim. Why did he say that about us?” I will never forget the look on this boy’s face, it was as if something within him was destroyed forever.

A third example occurred closer to home. During college move-in day at Georgetown University, one of my friends named Saria, a native of Syria, was moving into his freshman dorm room when he heard another freshman boy shout, “I hope there are no Syrians living in this dorm.”

The above examples are the consequences of not asking people their names, but rather assigning it to them. I have outlined stories across several continents on purpose. No place or group of people is immune to this type of incident. We must train ourselves to understand others’ plight and to be careful with our words. It is with these stories in mind that I realize there are two main problems related to the refugee crisis, number one, is obvious and more tangible: the physical and emotional needs of the refugees. The second problem, which I think it is just as important, yet less obvious, is how the rest of the world perceives and treats refugees, minority groups, and whoever may be labeled as “the other.”

The next two examples illustrate what can happen when we DO get to know each other’s names:

A student club at Hamburg High School in New York raised money to purchase a prefabricated house for a Syrian refugee family in Jordan. No one in this club had met a Syrian refugee prior to dedicating an entire year (including many weekends) to fundraising $3,000. However, they had learned the names and stories of the refugees and were inspired to take action. As a result Kareem, the 14-year-old boy who is pictured above, who was shot while he was walking to a bakery in Syria, received a new home in the Zaatari Refugee Camp.

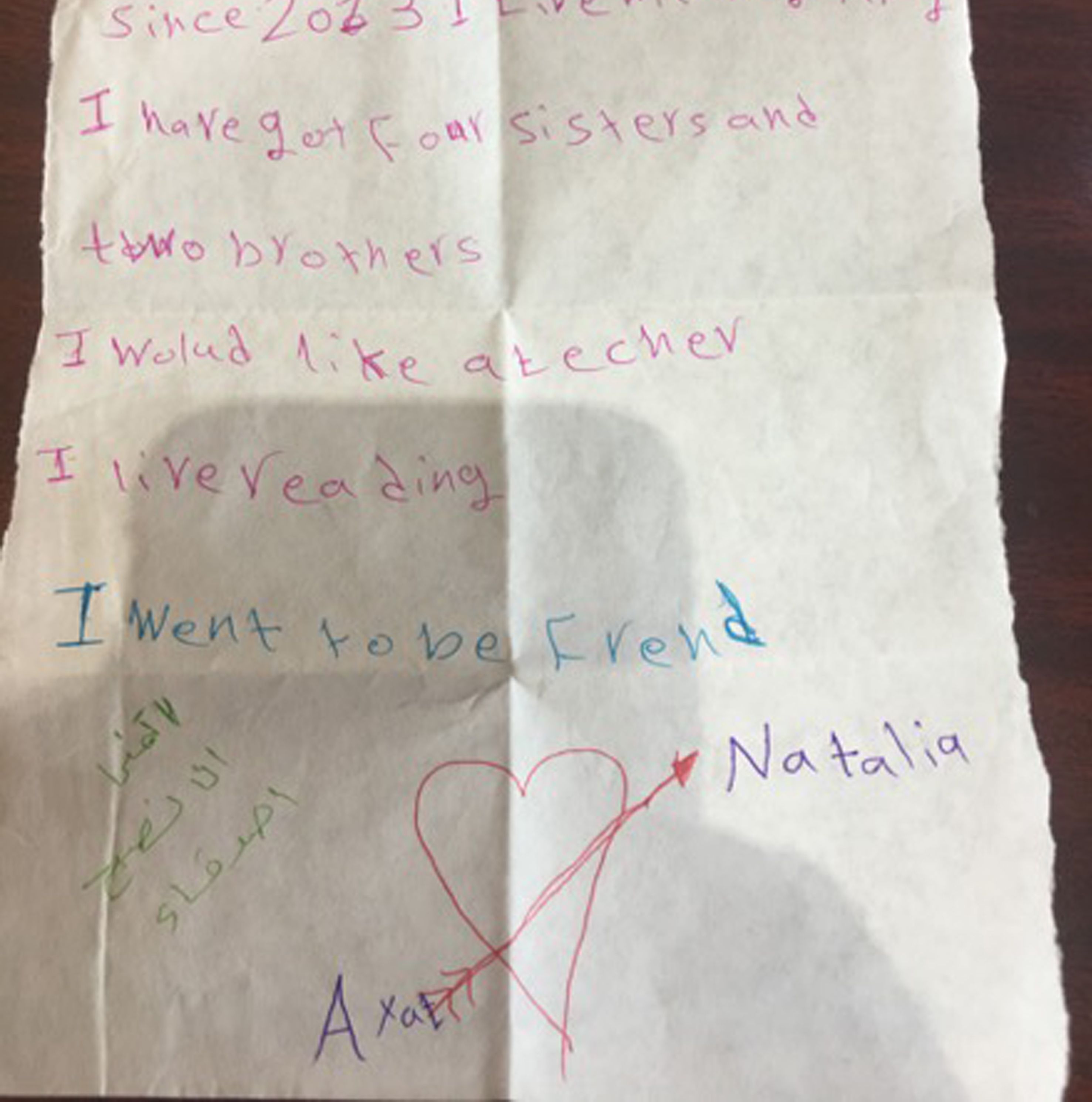

Another positive example of getting to know people’s names comes from a group of elementary students in Europe who wrote letters to Syrian refugee students. I delivered their letters to Syrian refugee students. Below is one of the actual responses that a Syrian refugee named Ayat wrote to Natalia, one of the European students.

The arrow that Ayat drew between the heart connecting her name with Natalia’s shows that the gift of friendship can start with knowing one’s name. And now, they are no longer just “a refugee girl” and a “European girl,” but rather friends because they took the time to ask each other their names.

It is not always easy or comfortable to ask someone their name or to share our own, but this gesture although small, can make a big difference in someone’s life.

Challenge for the month of September: Ask someone their name -- someone you wouldn’t usually ask.